What the eta meson does when no one's looking

(Originally published as a CMS Physics Briefing)

The amount of data that CMS has collected so far is truly astounding, thanks to the very large number of proton-proton collisions that the LHC has provided, over more than a decade, and to the large rate of events that CMS can record. And yet, even with so much data, some physics processes are so rare that they remain almost invisible. The decay of the $\eta$ (pronounced “eta”) meson into four muons (never seen until now) is a good example of such rare processes. A new CMS analysis has just resulted in its first observation, with a significance that exceeds the famous 5 sigma threshold. CMS also measured the corresponding branching fraction (the probability that the $\eta$ meson selects this particular channel to decay) to be $5 \times 10^{-9}$, a tiny number. This means that the four-muon decay of the $\eta$ happens only five times for every billion decays, so one really has to look hard for it.

The technique that enabled the observation of such a rare decay goes by the name of data scouting. The core tenet is that the fundamental limitation of data collection in CMS is not the number of events per second that can be recorded, but the amount of data that can be transferred to permanent storage. In other words, the data bandwidth bottleneck (well known to internet users around the world) leads to a smaller number of collected events if one insists on keeping all the information that exists in the events: every electron, muon, photon, and all the other particles produced in the proton-proton collision. This limitation implies that a lot of (interesting) events are discarded.

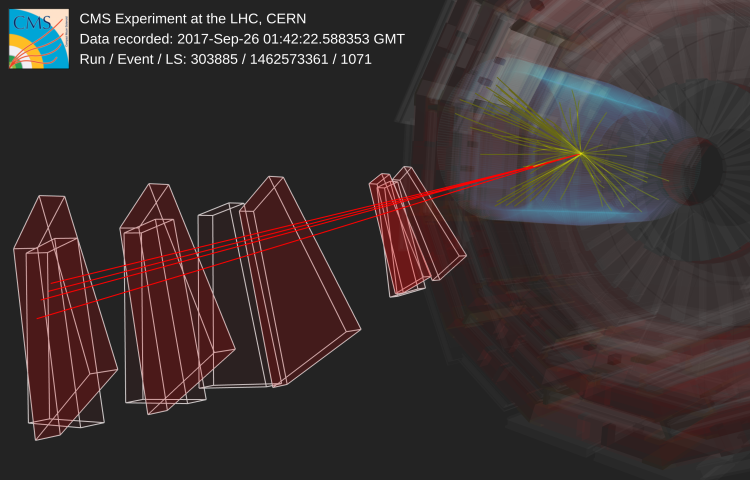

Data scouting neatly overcomes this limitation by only recording a fraction of the information. For example, we can decide that we only record the muons, in which case the size of each event is substantially reduced and, hence, we can store a lot more events. Figure 1 shows such an event, presenting a candidate four-muon $\eta$ decay. Of course, in this case one can only study physics processes leading to muons, but that’s ok because, luckily, that already covers a lot of interesting physics topics.

In practice, by using the scouting technique CMS can use significantly looser momentum thresholds in the double-muon triggers without exceeding the available data bandwidth. The double-muon scouting triggers require both muons to have a transverse momentum larger than 3 GeV, a much smaller threshold than the “standard” triggers (with typical thresholds of 17 GeV on one muon and 8 GeV on the other). This is particularly important for studies of very light particles, such as the $\eta$ meson, which has a mass of only 0.55 GeV. These mesons are copiously produced in the LHC collisions but their yields fall sharply with transverse momentum, so that they are almost nonexistent in the event samples collected with the standard triggers. Lowering the dimuon trigger thresholds is absolutely crucial to observe the very rare decays of the $\eta$.

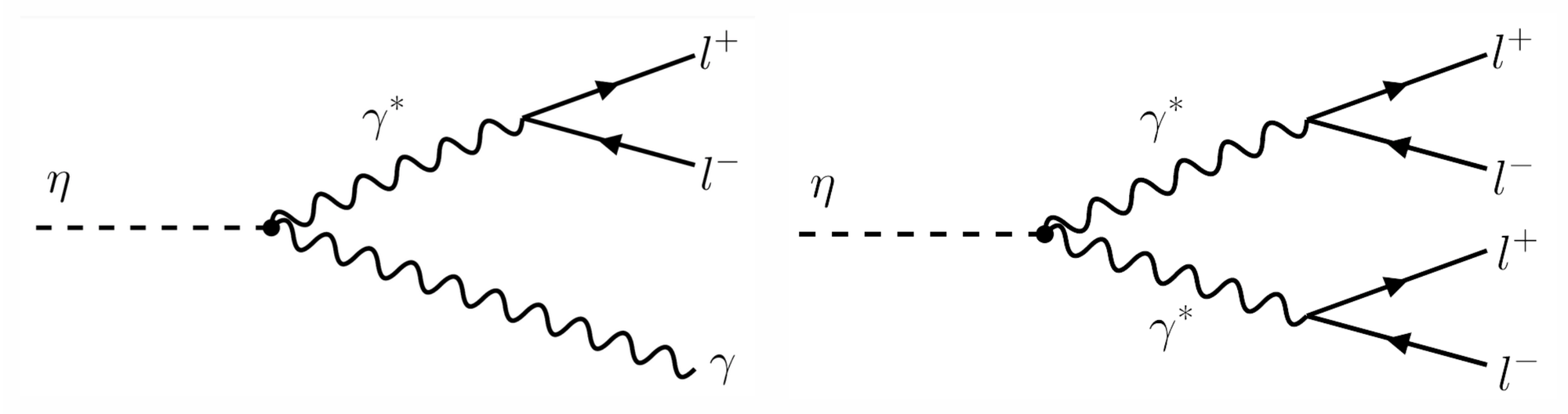

The four-muon $\eta$ decay belongs to the class of “Dalitz decays”, where a virtual photon is emitted and converts to a pair of leptons. Actually, it is a “double Dalitz decay”, because two virtual photons are emitted, leading to the four muons, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Such rare decays are interesting for several reasons: they could be sensitive to contributions from unknown particles; the coupling of the photon to the $\eta$ meson and other light mesons is one of the many ingredients entering the calculation of the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon; and one can use these rare decays as a test bed in searches for physics beyond what is known in the standard model of particle physics.

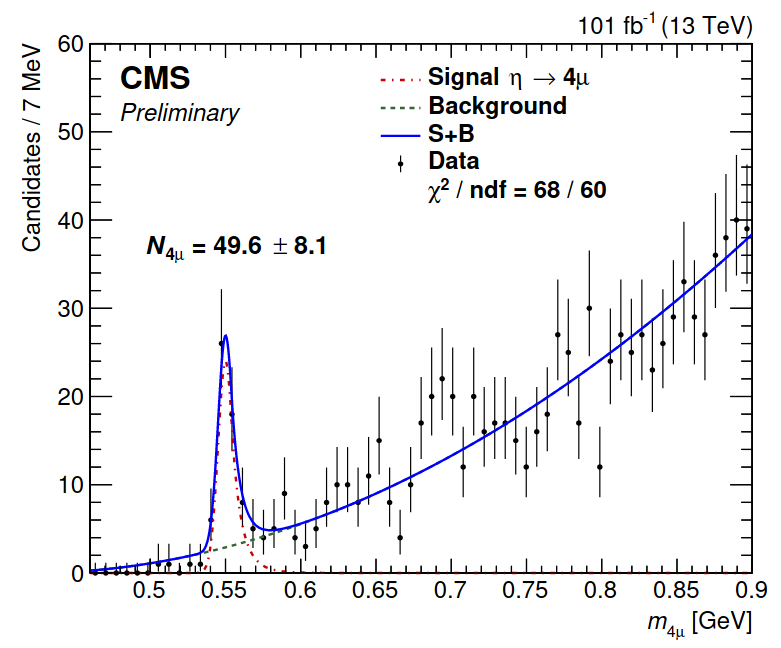

Using the scouting dataset, a clear peak is seen in the four-muon mass spectrum, shown in Fig. 3. The peak is located at the mass of the $\eta$ meson, which is, of course, no coincidence! About 50 events contribute to the peak. The branching fraction of the newly observed decay channel can be measured with respect to the well-known two-muon $\eta$ decay, also seen (much more easily) in the data. The only important ingredient needed for that measurement is a good understanding of the detection efficiencies, for each of the two decay channels. They were evaluated using a detailed simulation of the CMS detector response to the two processes. The measurement gives a branching fraction of the $\eta$ to four muons decay channel of $(5.0 \pm 1.3) \times 10^{-9}$, a value in agreement with theoretical estimates, within the quoted uncertainties. Future measurements, to be made with scouting data samples being collected in Run 3, will have a significantly improved precision, enabling a more refined comparison with the predictions.

This observation of a new decay channel and the measurement of its tiny branching fraction constitute a clear example of the immense value of scouting datasets in CMS.